Drawings

How to Draw: Archaeology Version

by Yolanda Peláez Castellanos

Part 1: The Field

Archaeologists are responsible for recording everything that they find as the materials could provide valuable research information not only about the context but also about past human activities. Once the materials are completely registered, they are removed from their original context. For that reason, it is essential to record as much information as possible out in the field. Field drawings are part of this registering process, and that includes having the context drawn by hand, capturing the ‘what’ and ‘how’ the archaeologist encountered the excavation area.

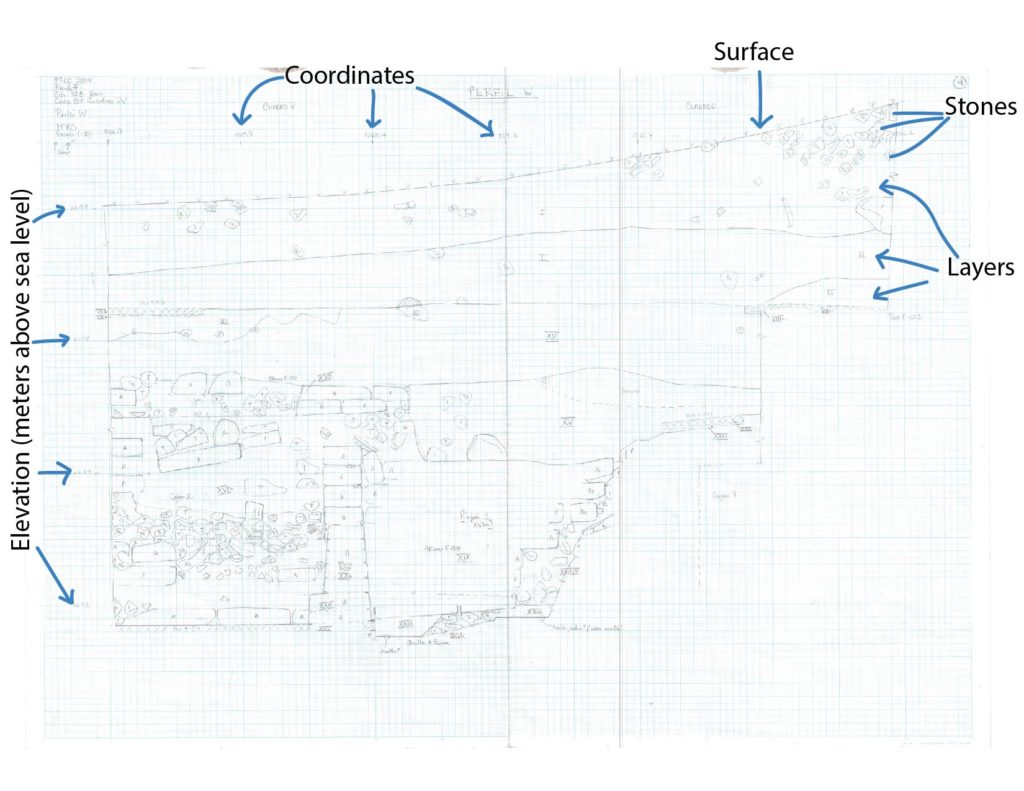

Profile drawings

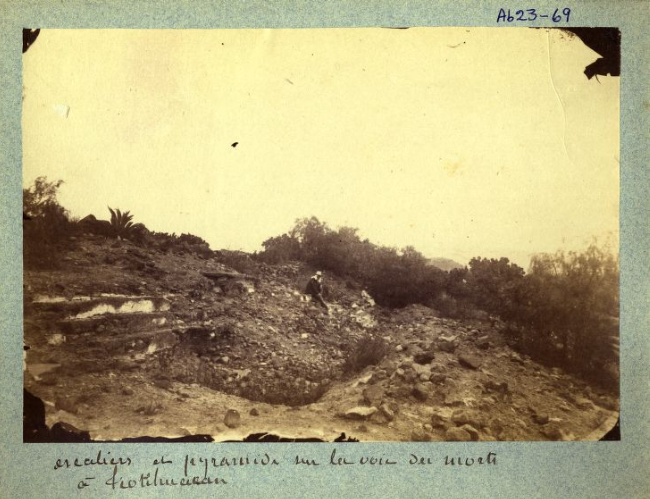

Have you ever driven through a mountainous landscape and observed the different shades of sediment peeking out of the exposed mountain rock?

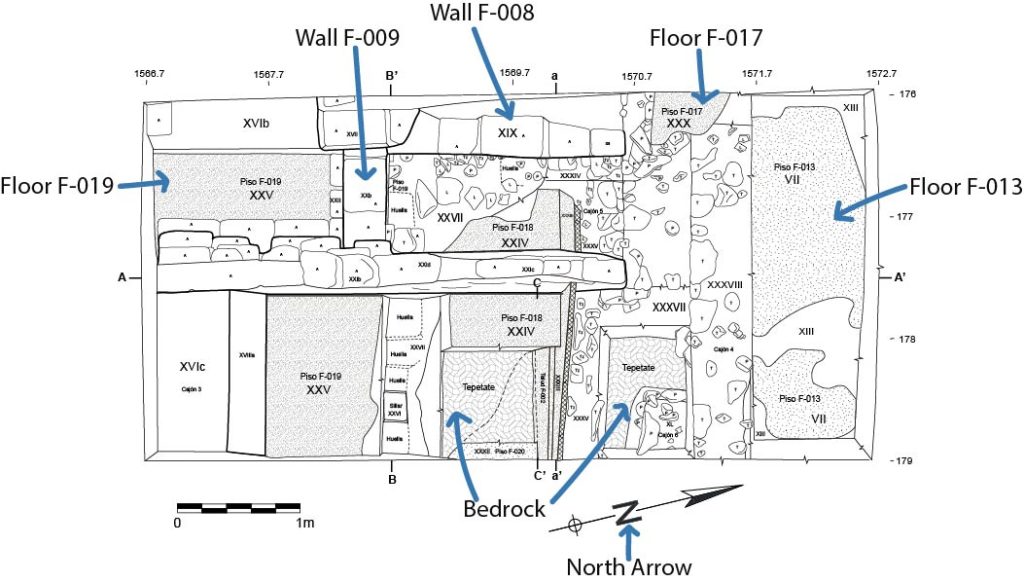

Well, back to archaeology. Think of the term “profile” as the excavation unit’s “walls.” The rock or layered sediments you see actually resemble an excavation profile. Profile drawings are important for understanding the pit’s history as different periods of time are captured by the various colors of sediments and their composition. When you combine this information with architectural and human modifications of the landscape, they can help us to understand if a structure collapsed, whether it was an intrusion or looting activity, as well as where architectonic elements (floors, walls, canals) were spatially and chronologically located. Visit the Excavations section to read more about stratigraphy.

Why are drawings even necessary? Can’t archaeologists just take photos?

Drawings and photographs complement each other when studying an area. Although photographs do capture color, they are taken at certain angles, limiting what is taken within each frame. On the other hand, profile drawings are accurate and do not distort what is being recorded; the drawings are drawn precisely and to scale. Additionally, sometimes there are profile details that can be better appreciated in person but are not clear in photos.

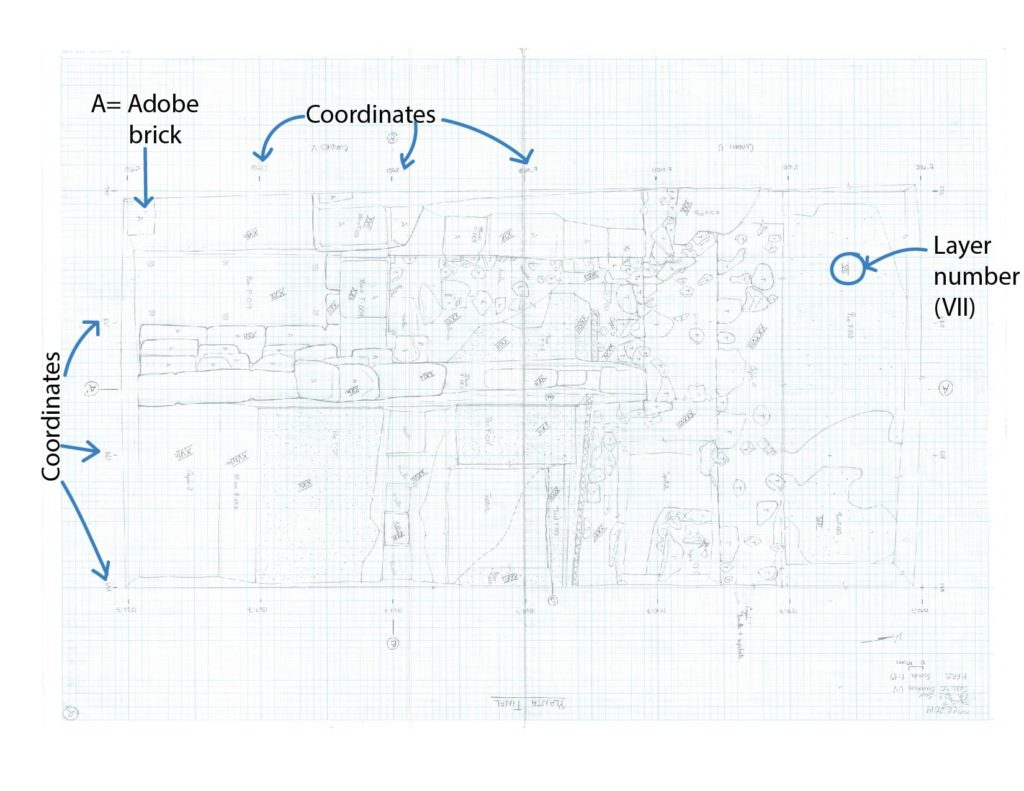

Plan drawings

These drawings show the excavation unit from above, a bird’s eye view. They depict the distribution of different architectonic elements and their relationship with each other.

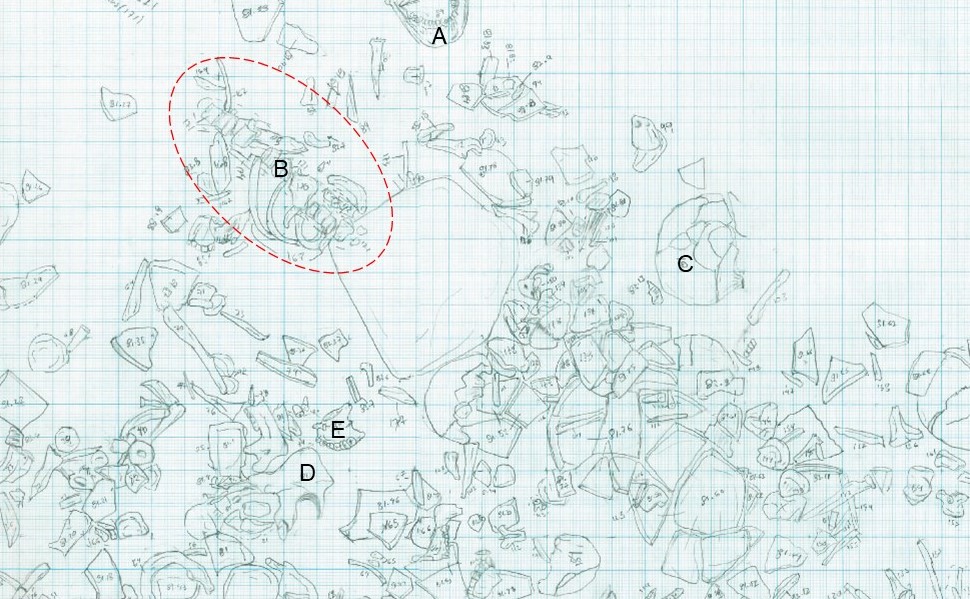

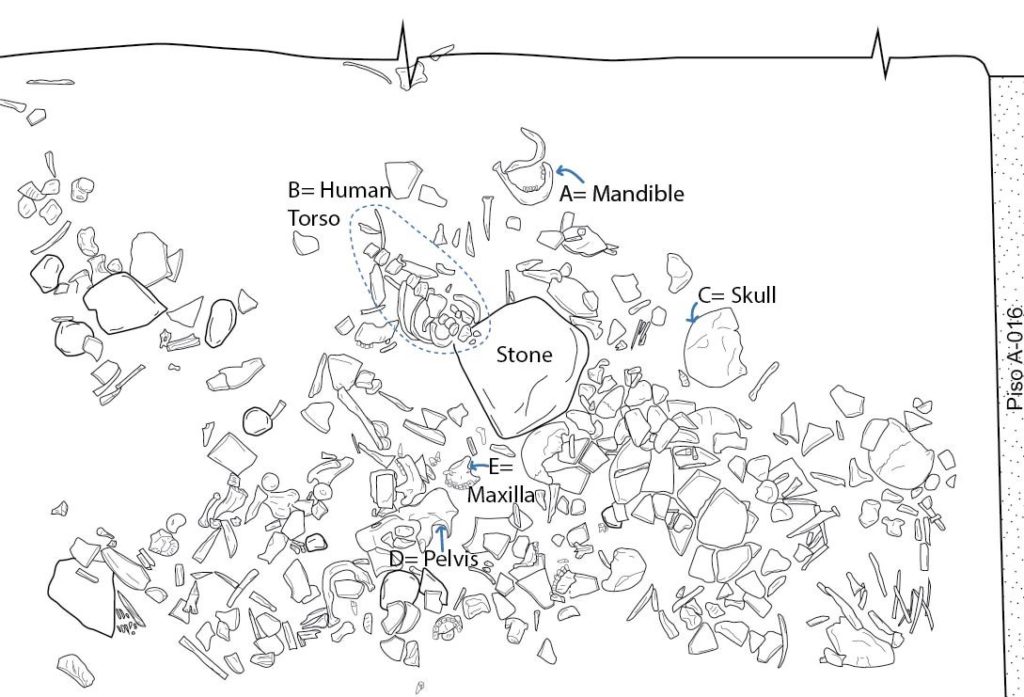

Special contexts

Special contexts that show evidence of human activities, like burials, trash pits, and offerings, are also recorded as detailed plan drawings. In these cases, the exact location and thus distribution of each artifact is drawn and assigned a unique number before its removal from the excavation area. The following image is the drawing of a context excavated in Front A (see Results 2018-2019) that had thousands of disarticulated (mostly human) bones. Can you identify some of them (A-E)?

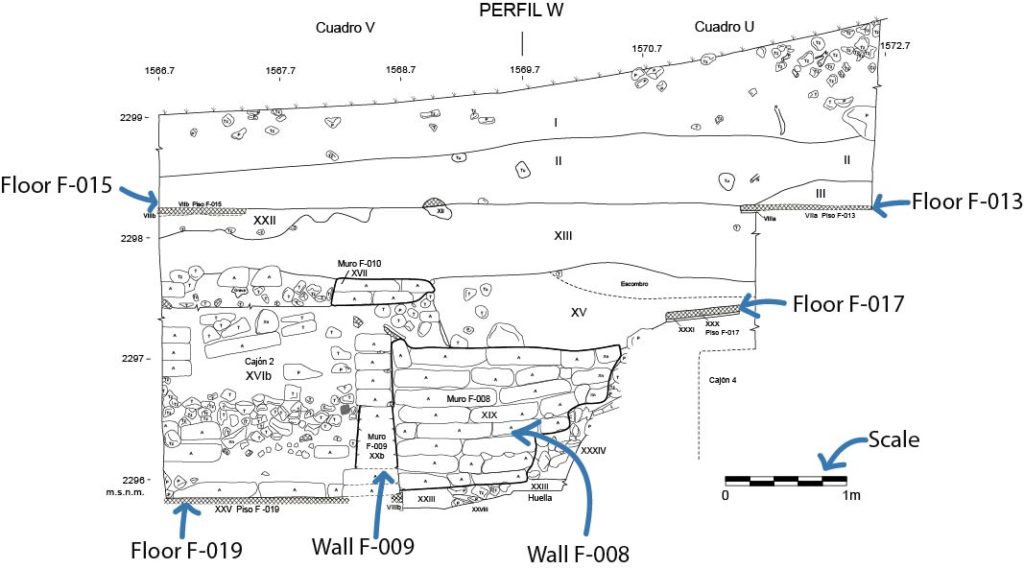

Part 2: Digitalization

Digitalization is the process in which field drawings are converted from freeform into a digital form that can be processed by a computer. All field drawings are scanned at the end of each field season for two important reasons: to preserve and to refine field drawings (as a digital format) without changing or losing the original copy.

Each field drawing is scanned and digitally traced using illustration software such as Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, or Corel Draw. This way, final drawings are clean, clear, and complete with pertinent details.

Look at the digitalized profile and plan drawings below. The arrows point to architectural features (i.e., floors, adobe brick walls). Notice that Floor F-015 is missing from the plan drawing. It had to be removed to uncover what was beneath but remained visible in the profile. The vertical (profile drawings) and horizontal (plan drawings) representations show different details, and both are important for understanding the context. If you want to learn more about this excavation area located in the southeastern section of Front F, visit the Results 2018-2019 section.

Were your guesses on the bones from Front A’s special context correct? Although these materials are still being analyzed, the drawings will be helpful for interpreting the context because they depict the material’s spatial distribution across the excavated area.

Example of a digitized drawing of a special archaeological context (Drawing by Ariel Texis and Yolanda Peláez).

Part 3: Artifact Drawings in the Lab

Many archaeological materials are recovered in every excavation season, and realistically not all materials are drawn as they can be abundant. While analyzing the artifacts, archaeologists and specialists select those for illustration, usually artifacts that are representative of other excavated material and/or are unique to the context.

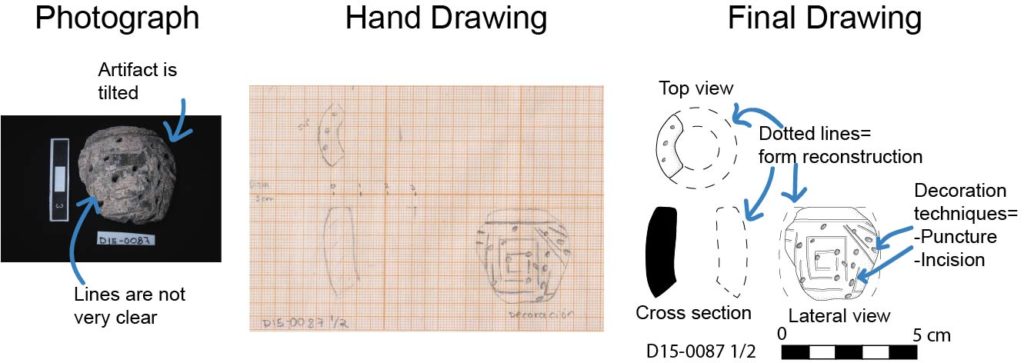

The drawing process in the lab is similar to field drawings. Artifacts are first drawn in pencil on a grid paper, allowing for ease of precise measurements and thus to scale. By handling and observing the artifacts in person, the illustrator can capture acute details that may not have been distinguishable through photographs. Afterwards, the drawings are scanned and drawn digitally or traced by hand with ink.

What kind of information can artifact drawings provide?

A lot! The type of information depends on the artifact, but it is usually related to the object’s manufacture or use:

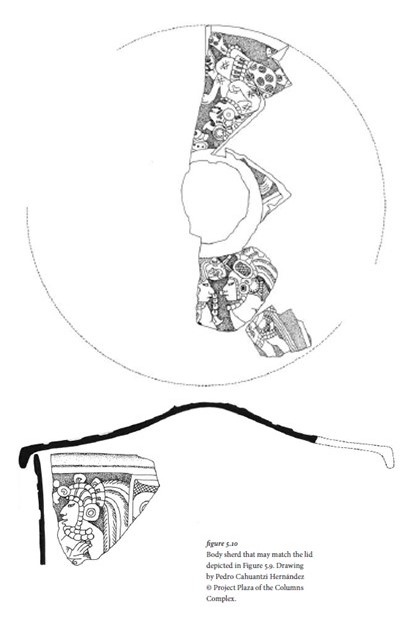

- Ceramic is the most abundant material in our excavations, and their drawings demonstrate their various shapes, decorative techniques, and iconographies.

- Lithic drawings can show the methodical steps in which the raw stone materials themselves were modified, including the decisions made by the artisans themselves (e.g., touchups).

- Bone drawings depict their anatomy and highlight surface modifications made by humans (e.g., butchery marks, toolmaking).

While archaeological artifacts are usually fragmented, certain pieces (e.g., ceramic rims) can be used to reconstruct what the complete vessel might have looked like. Reconstructions are usually delineated by a dotted line.

Conclusion

Archaeologists meticulously draw the details they see both in the field and in the lab. Since observation is one of the steps of the scientific method, archaeological drawings are essential because they contribute to this research process. Moreover, they are a way of preserving cultural heritage in various forms, not only in a two-dimensional sense but also in a digital format to capture multiple perspectives on a snapshot of history.

References

Pngegg

n.d. Highland Landscape Landform Plain Plateau, Mountain Landscape 2, natural, grass. Electronic document, https://www.pngegg.com/en/png-boaxc, accessed August 18, 2021.

Sugiyama, Nawa, William L. Fash, Barbara Fash, and Saburo Sugiyama

2020 The Maya at Teotihuacan? New insights into Teotihuacan-Maya interactions from Plaza of the Columns Complex. Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City, edited by Kenneth Hirth, David Carballo, and Barbara Arroyo, pp.139-171, Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Symposia and Colloquia series, Dumbarton Oaks Reserch Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.