Ancient urban alignment leads LiDAR investigation to new site

By Alexis Bridges, Tanya Catignani y Ariel Texis Muñoz

At Teotihuacan the use of detailed satellite imagery and LiDAR technology has allowed for remote detection of archaeological features which are often impossible to see at ground level. It affirms that we can neither escape the legacy of the past nor the influences that it has on our present.

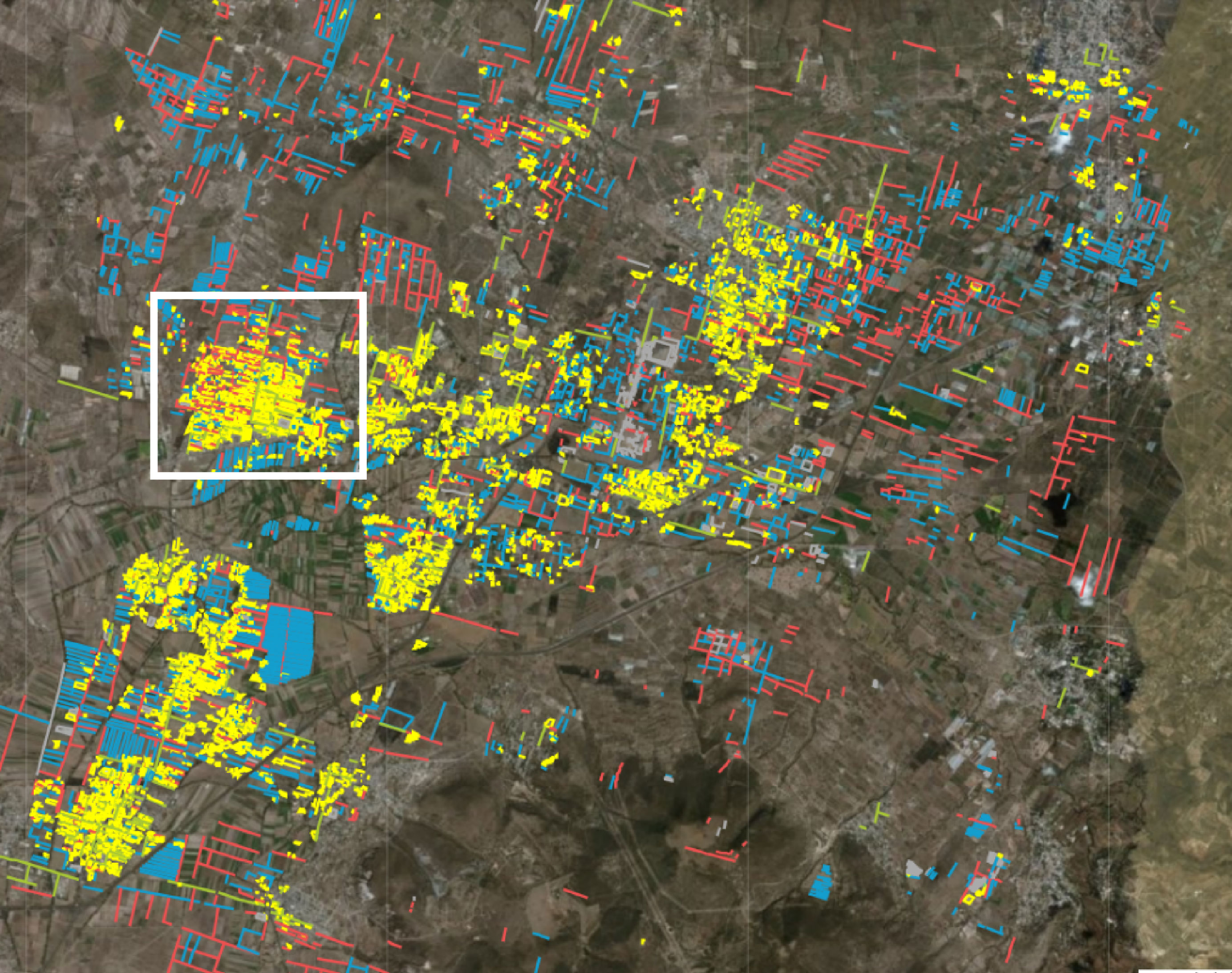

One of the goals of the Project Plaza of the Columns Complex this season has been to determine how much of the present-day Teotihuacan Valley was influenced by the ancient alignment of 15 degrees east of true north. Our team tracked this alignment by digitizing modern features in ArcGIS Online (Figure 1). Because the Avenue of the Dead is so central to the city, it seemed logical that nearby modern structures would be aligned in the same configuration, and areas farther away from the city center would less likely display this pattern. Our results abiding by the strictest of calculations revealed that more than 30% of the region does match this traditional alignment, even areas that are far away from the city center. One theory for this is that ancient structures, long crumbled and buried over the centuries since their initial construction, may have influenced contemporary building and agricultural decisions by raising complications of digging and plowing around these archaeological features.

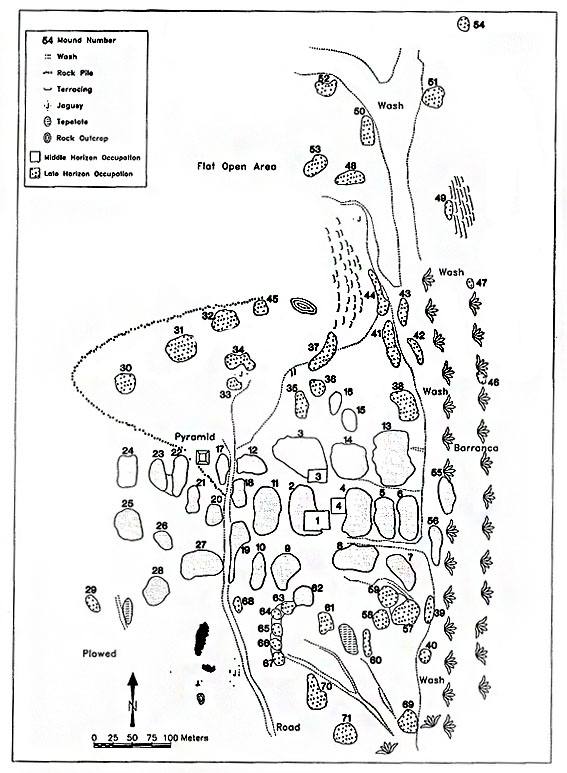

One town in particular that drew our attention lies to the west of the city center (see Figure 1). Nearly all of the town is aligned, resulting in a massive hotspot of digitized features on the map. However, the LiDAR and satellite maps did not reveal any obvious archaeological features in the area. After studying old archaeological reports, we found that this location had, indeed, been previously excavated. In the 1960s William T. Sanders discovered an apartment compound capable of housing hundreds of people at its peak occupation and was inhabited at least until the Colonial period (Figure 2). Although Sanders’ team identified this site as TC-8, the eighth site associated with the Teotihuacan Classic period, his site map lacked identifiable features that could have led us to the excavation site.

Despite this, Sanders created a second map that charted the entire valley, fortunately safeguarding sites that may have disappeared over time. A rough location of the site was found by georeferencing what streets and towns still existed. From there, a rock alignment could be seen on the LiDAR map as well as very, very slight mound formations that closely matched with the ones identified on Sanders’ map (Figure 3).

Preliminary ground truthing has yielded promising results of pottery sherds and shell fragments ̶ an unusual find for an inland area. Using a similar process, another site in the southwest known as TC-21 was also located with similar finds of ceramic sherds. Although these preliminary results are not confirmation, they do indicate that our locations may be these previously forgotten Sanders’ sites.

This experience highlights the power of combining modern technology with historic data. Technology without the analog aspects of archaeology cannot show us everything, and relying entirely on technology will create a loss of data. The re-discovery of TC-8 and TC-21 only shows that archaeology is, and will likely remain, a historical science at its foundation.