Early Images of Teotihuacan in the Modern Era

by Yolanda Peláez Castellanos

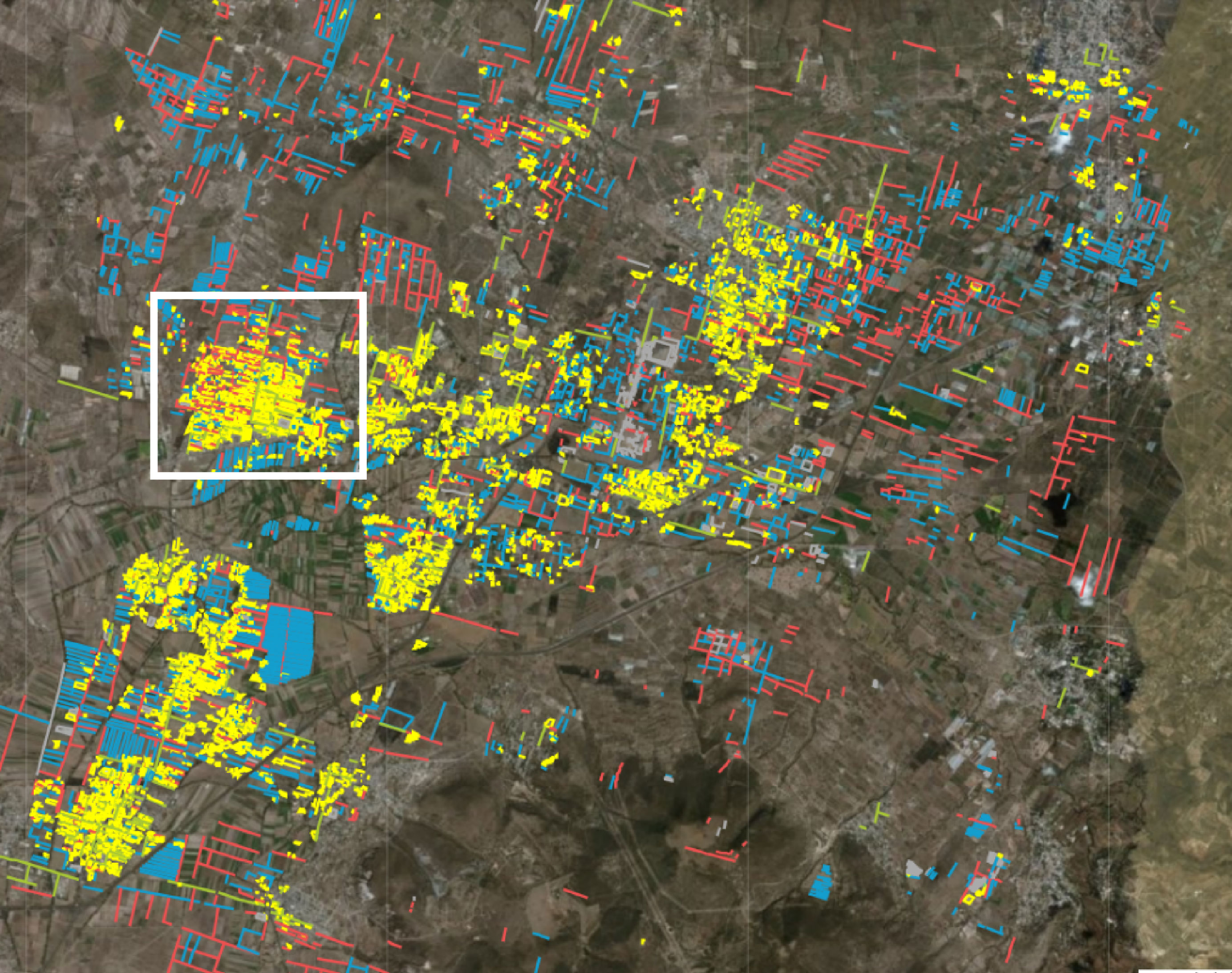

Today, it is very easy to photograph and document the world around us. For example, people visiting Teotihuacan can take countless photos and share them on social media immediately; however, in the past, it was much harder to capture and reproduce images. The lithographs, paintings, and photographs from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century demonstrate the many changes that the archaeological zone of Teotihuacan has undergone. Most of the images here can be found at INAH’s Media Library.

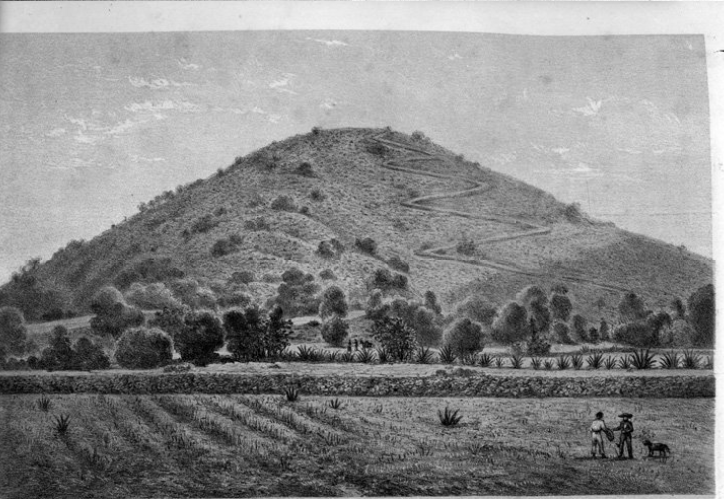

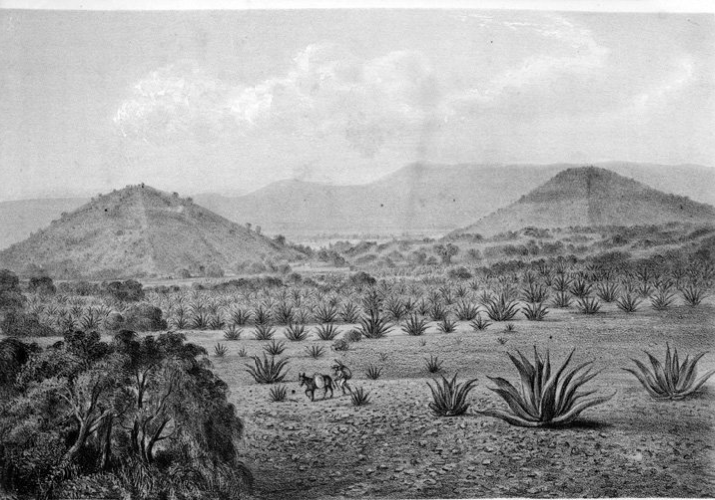

Developed in the late 18th century, lithography is a printing method which has been used to preserve images that explorers saw. In lithography, an image is engraved on a surface (usually limestone), ink is applied, and then the stone is pressed into paper (Tate 2021). This process allowed for a wider distribution of images of sites such as the Teotihuacan pyramids and its scenery during the 19th century.

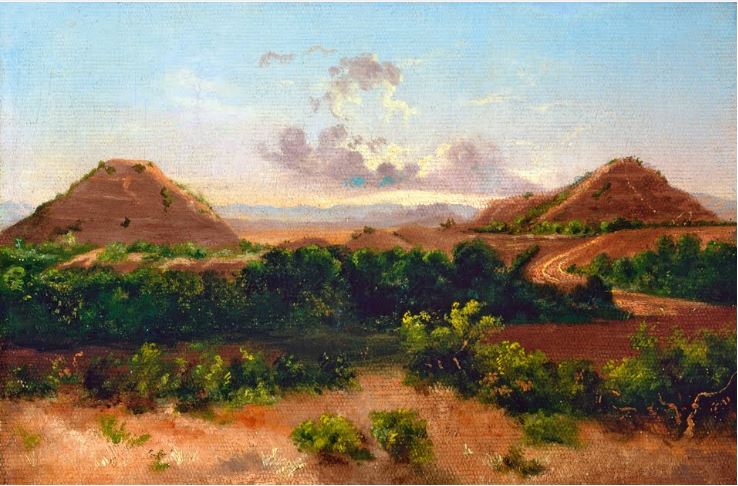

José María Velasco (1840-1912) was a Mexican painter who accompanied Gumesindo Mendoza in his expeditions to Teotihuacan and portrayed the city’s landscape in his paintings (Google Arts and Culture s.f.). Teotihuacan was abandoned around AD 550, so after some 1,300 years had passed, there was certainly a lot more vegetation covering the monuments for Velasco to capture.

© Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

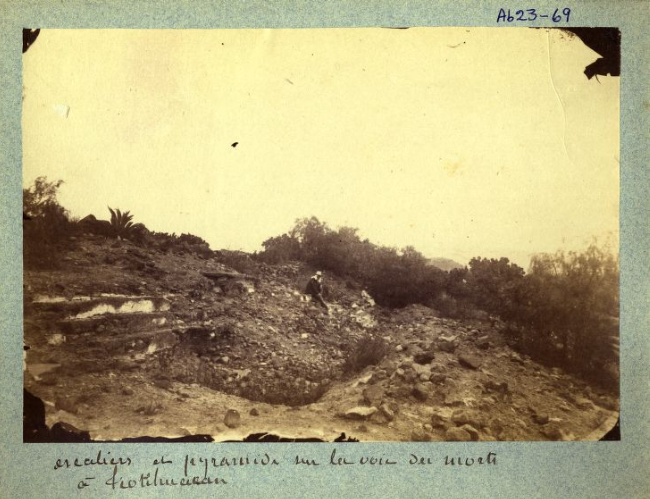

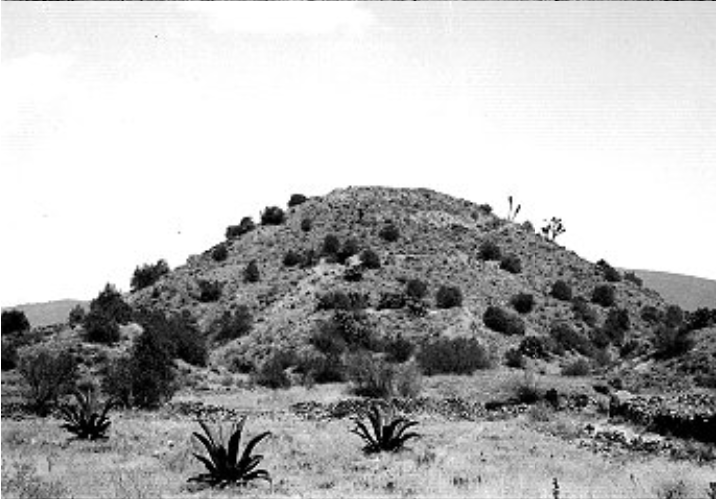

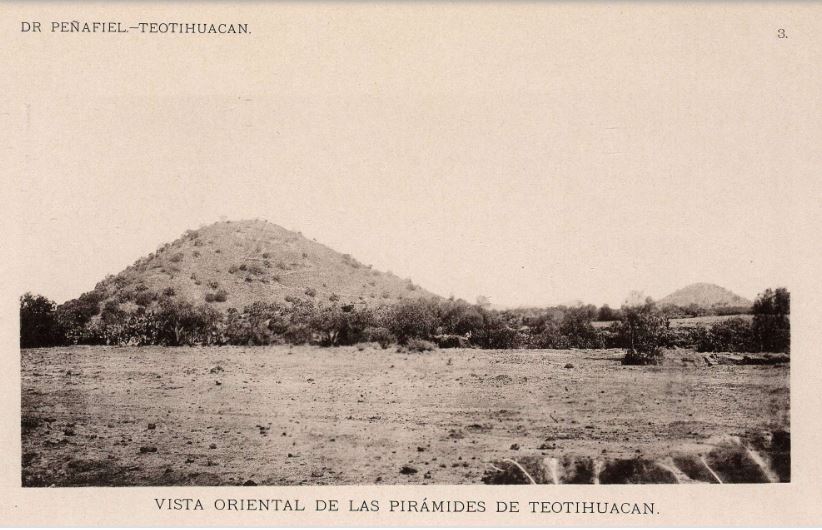

Here are some bonus photographs of the site (way back in the day) for you to enjoy:

© Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

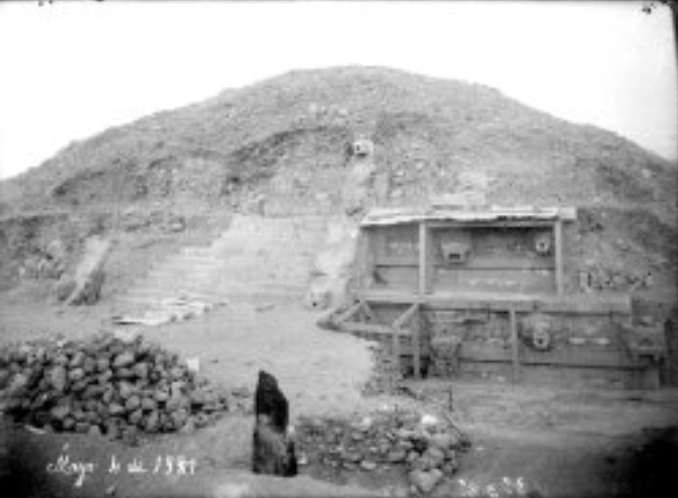

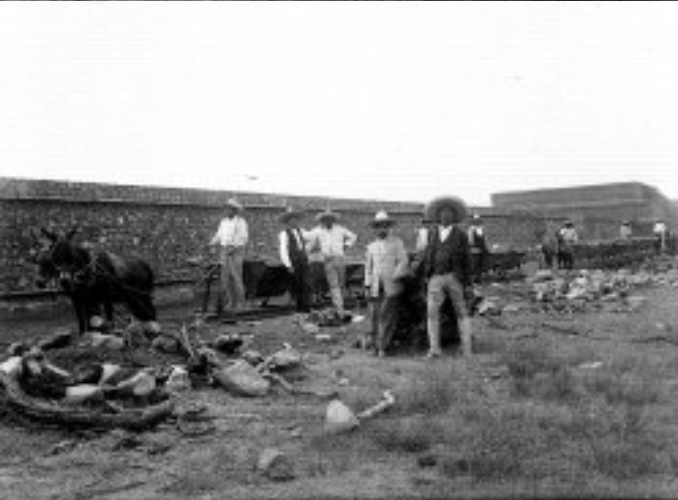

The first archaeological work began on site in the early 20th century by Leopoldo Batres to commemorate the centennial of the Mexican War of Independence. Batres was commissioned by President Porfirio Díaz to explore and restore some of Teotihuacan’s monuments. This project included reconstructing the Sun Pyramid, building railway lines, and discovering murals in the Temple of Agriculture (Batres 1993 [1919]).

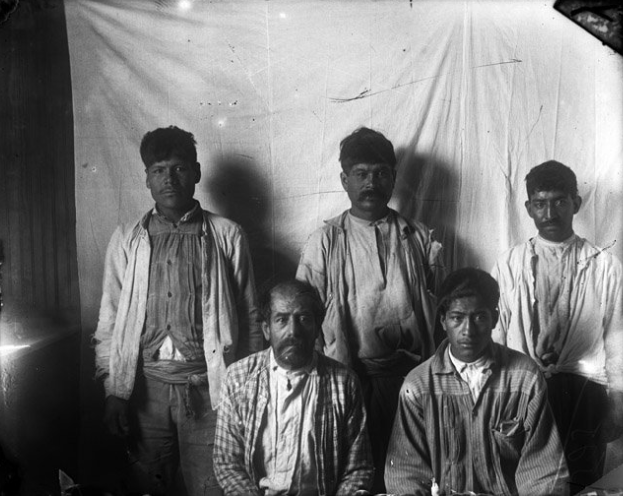

Seeing the clothes that people wore back then is a testament to how much time has passed. Indeed, fashion has changed since.

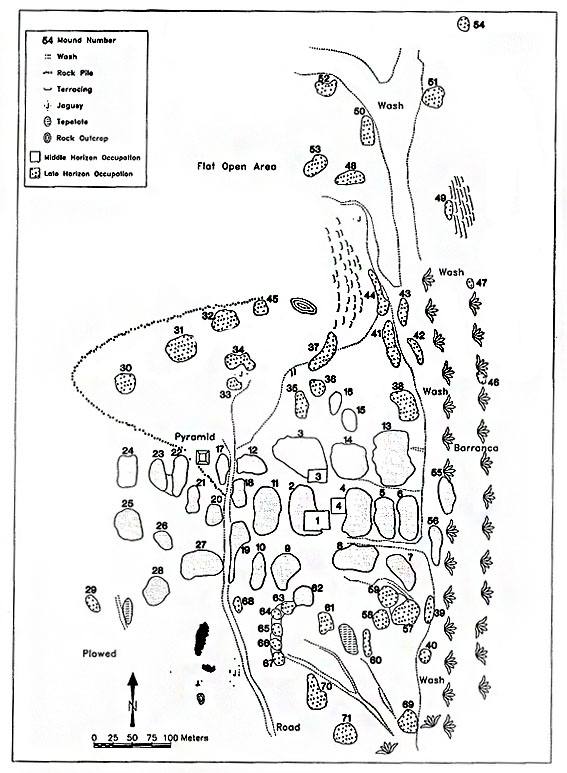

The excavation, restoration, and reconstruction of Teotihuacan continued through the 20th century. The rest of the photographs here likely refer to:

- The project directed by Manuel Gamio where he carried out a comprehensive study of the population in the Teotihuacan Valley (Gamio 1922). Some of the work his team accomplished include the excavations of the Ciudadela as well as the exploration and restoration of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid and its attached adosada (Figures 15-17).

- Excavated pits in the Ciudadela and tunnels in the Feathered Serpent Pyramid by José Pérez under the direction of Alfonso Caso (Pérez 1997:488 [1939]) (Figure 18).

- The Teotihuacan Project directed by Ignacio Bernal, head of the Department of Prehispanic Monuments. Although some of the buildings were excavated to learn more about their history, most of them were reconstructed so they could be restored back to the last occupational phase look (Bernal 1997 [1963]) (Figures 19 and 20).

These images document how much change Teotihuacan had undergone in the first half of the 20th century. Although several centuries have passed since its occupation during the Classic period, this site continues to be relevant in the construction of our history. To know more about the history of this pre-Hispanic city, you can check the PPCC’s study area section.

References

Bernal, Ignacio

1997[1963] Teotihuacan: descubrimientos y reconstrucciones. In Antología de documentos para la historia de la arqueología de Teotihuacan, compiled by Roberto Gallegos Ruiz, José Roberto Gallegos Téllez Rojo, and Miguel Gabriel Pastrana Flores, pp. 594-615. National Institute of Anthropology and History, Mexico, D.F.

Batres, Leopoldo

1993 [1919] The “Discovery” of the Sun Pyramid. Arqueología Mexicana 2:45-48.

Gamio, Manuel

1922 La población del valle de Teotihuacan, Vol. I, 1. Dirección de Antropología, Secretaría de Agricultura y Fomento, Mexico, D.F.

Google Arts and Culture

s.f. Teotihuacan. Electronic document, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/teotihuacan/KgEZFx_-t8JNxQ?hl=es-419, accessed February 23, 2021.

Pérez, José

1997[1939] Informe de los trabajos de Alfonso Caso y José R. Pérez. In Antología de documentos para la historia de la arqueología de Teotihuacan, compiled by Roberto Gallegos Ruiz, José Roberto Gallegos Téllez Rojo, and Miguel Gabriel Pastrana Flores, pp. 488-498. National Institute of Anthropology and History, Mexico, D.F.

Tate

2021 Art Term: Lithography. Electronic document, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/l/lithography, accessed February 24, 2021.