The Elements of a Paleodiet: How Isotope Analysis Help Archaeologists in the Lab

by Esther Aguayo

Food is an important part of our lives, yet it is a difficult thing to see in the archaeological record. Usually archaeologists rummage through ancient trash piles to look for animal bones and residues in pots to find out what people ate. However, there is another tool that archaeologists use that can tell us more about what people and animals consumed called stable isotope analysis. This methodology helps archaeologists understand the chemical make-up of human and animal bones to reveal information regarding diet, social organization, and human-animal interactions. At the Archaeological Sciences Lab at George Mason University, I help prepare bones in order to extract that information.

All living organisms are comprised of molecules that they have absorbed or eaten throughout their lives. Bones, teeth, and even hair molecules can tell archaeologists a lot about an organism’s life history and environment. These molecules, referred to as stable isotopes, and their composition can vary depending on the environment of the organism. Factors such as temperature, altitude, nutrition, and humidity affect isotopic composition and will be reflected in the tissues we look at. There are several isotopes that can be analyzed such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and strontium.

Carbon is most familiar as the lead in our pencils and what we breathe out in carbon dioxide, but carbon also relates to the way plants obtain energy or photosynthesis. C3 and C4 cycles are the most common photosynthetic pathways a plant can use and can be determined from bones of an animal or person who ate plants. Since photosynthesis varies among plants, archaeologists can reconstruct what people and animals were eating, where they lived (based off where the plants grew), and how their diet changed over time. This is the information that can be deduced from carbon alone. It is important to collect the information stable isotope analysis provides. So, how do archaeologists conduct isotope analyses?

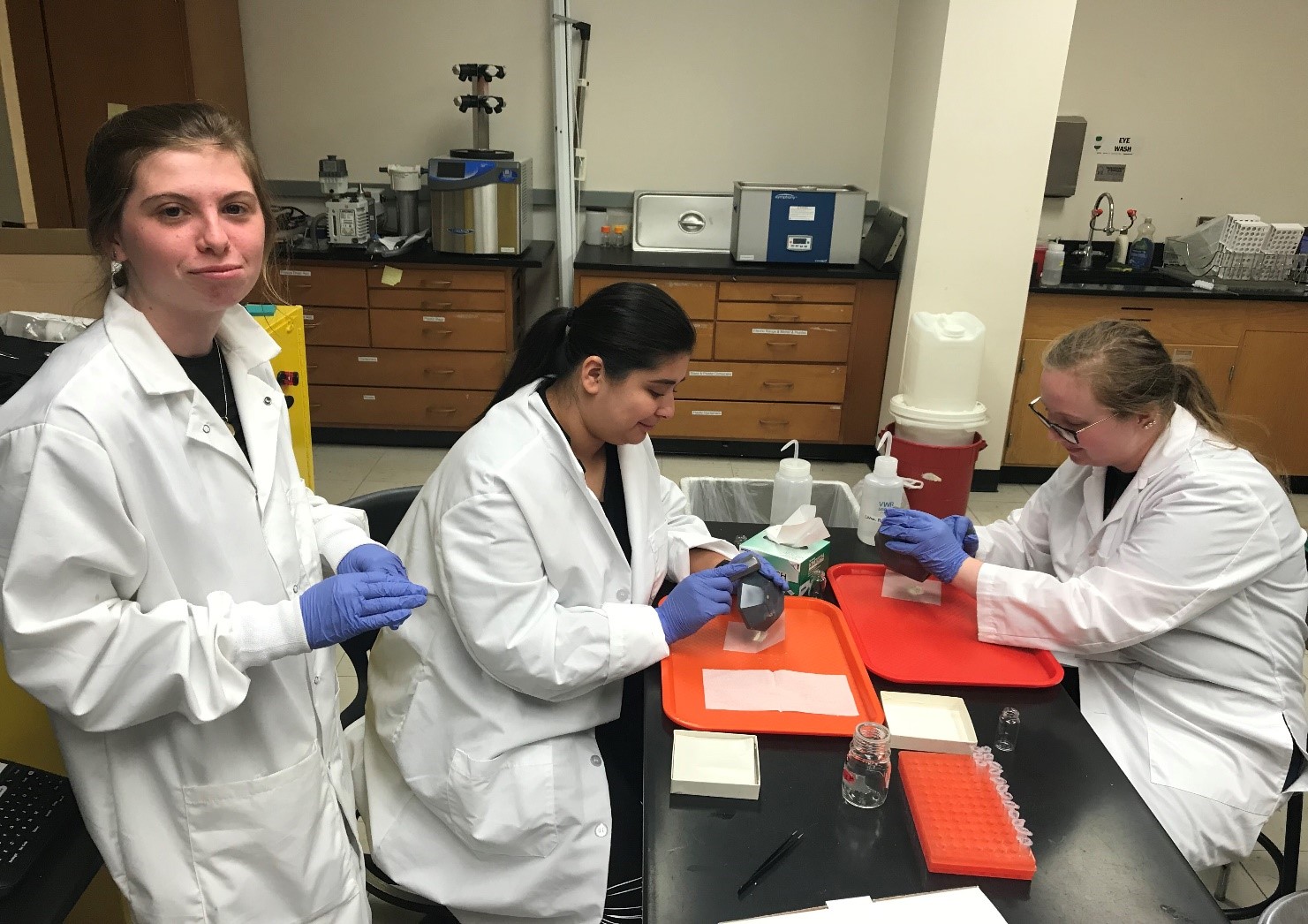

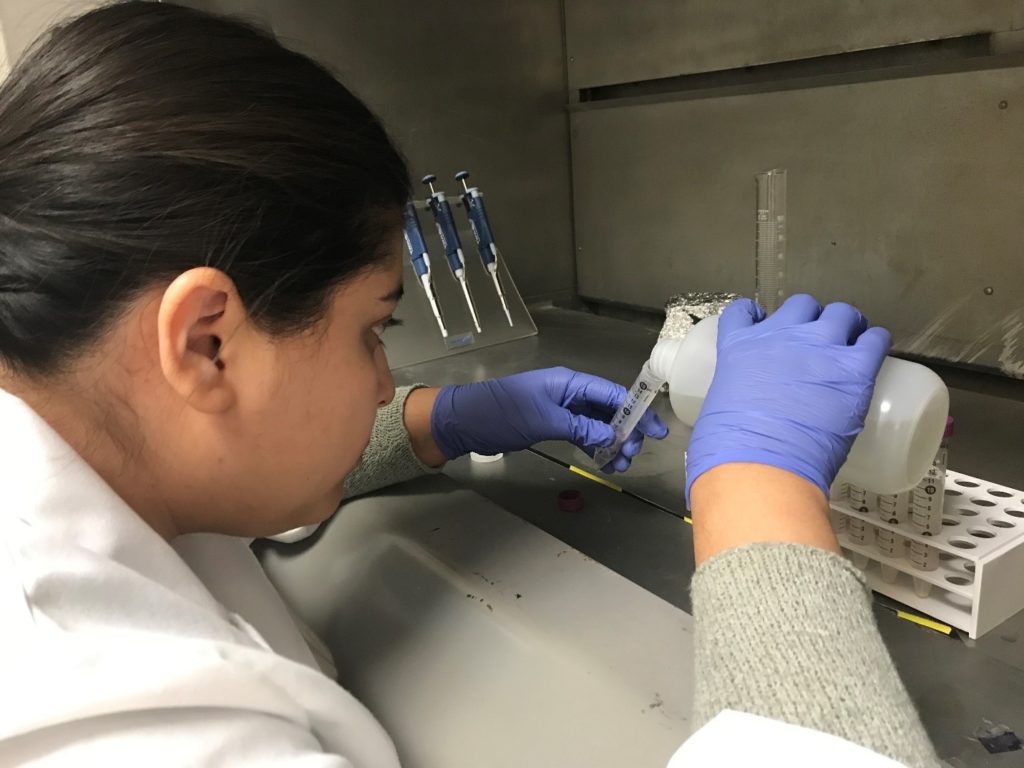

In the Archaeological Sciences Lab I help prepare the bones to extract the isotopic information we need. The bones from the Project Plaza of the Columns Complex (PPCC) are cleaned after excavation. Then, the bones are analyzed, identified to species, photographed, and documented for further reference. It is important to document the bones well because isotope analysis is a destructive process. First, I make sure the bones are cleaned completely. Using a hand rotary tool, I thoroughly clean off any excess dirt and build-up on and inside the bone. I also use the rotary tool to remove a part of the bone that will be used for the isotopic analysis. Then, I wash the bones in a sonic bath which uses high frequency sound waves to remove any remaining dirt that cannot be removed by hand.

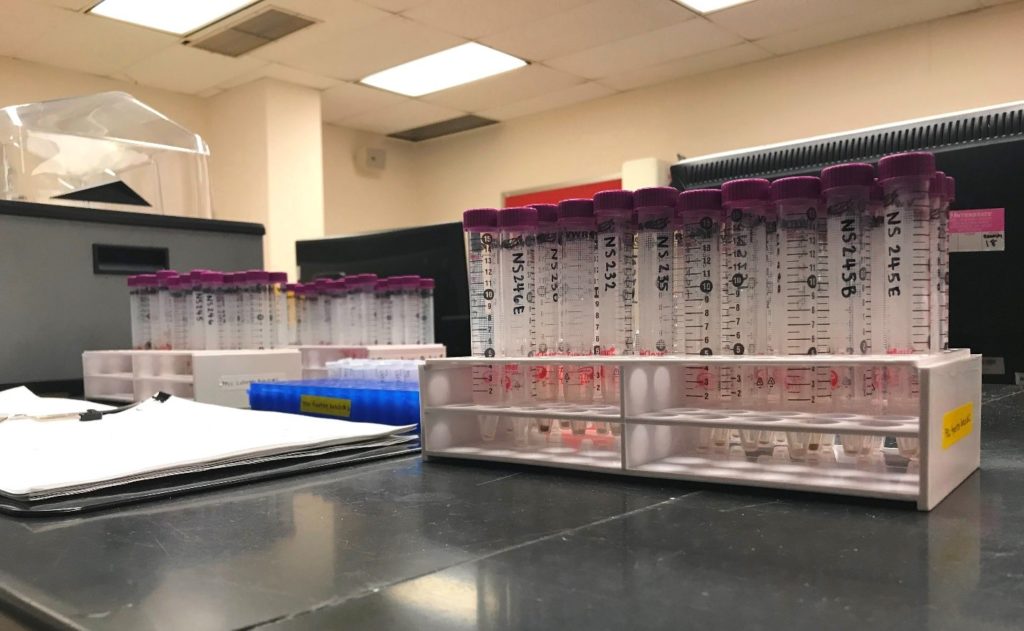

After letting the bones dry overnight, I use an agate mortar and pestle to crush the bones into a fine powder. I weigh each sample and transfer them to tubes so they may soak overnight in a chemical solution to begin the removal of organic components. Then, the samples are rinsed in ultrapure water, and an acid solution is used to completely remove all organics in the sample. Once weighed a final time, the sample is ready for the mass spectrometer at the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute. The mass spectrometer is able to measure isotopic variations in a sample. It is through those variations that archaeologists can gain insight on the diet of the individual and the ecosystem they lived in.

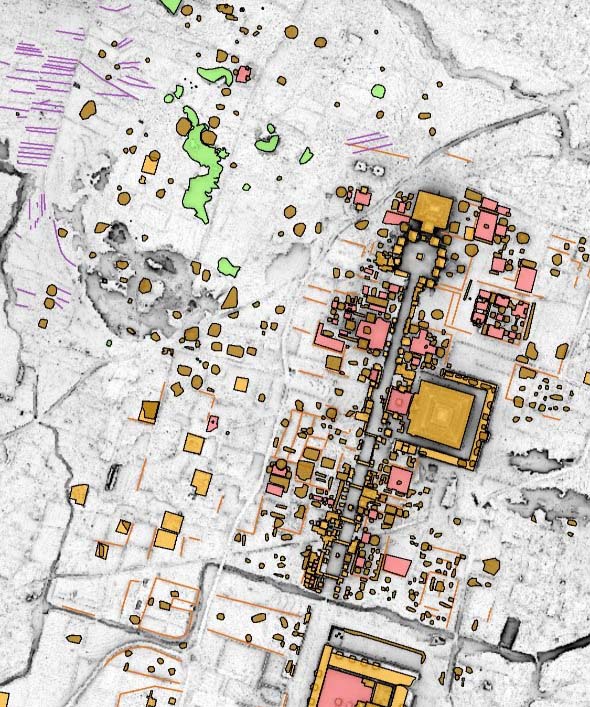

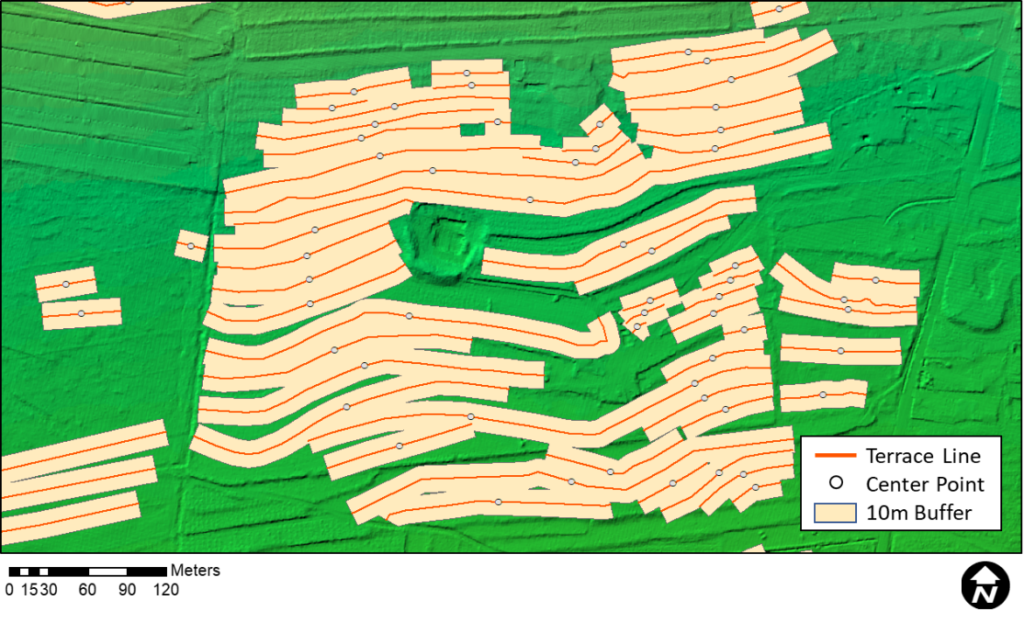

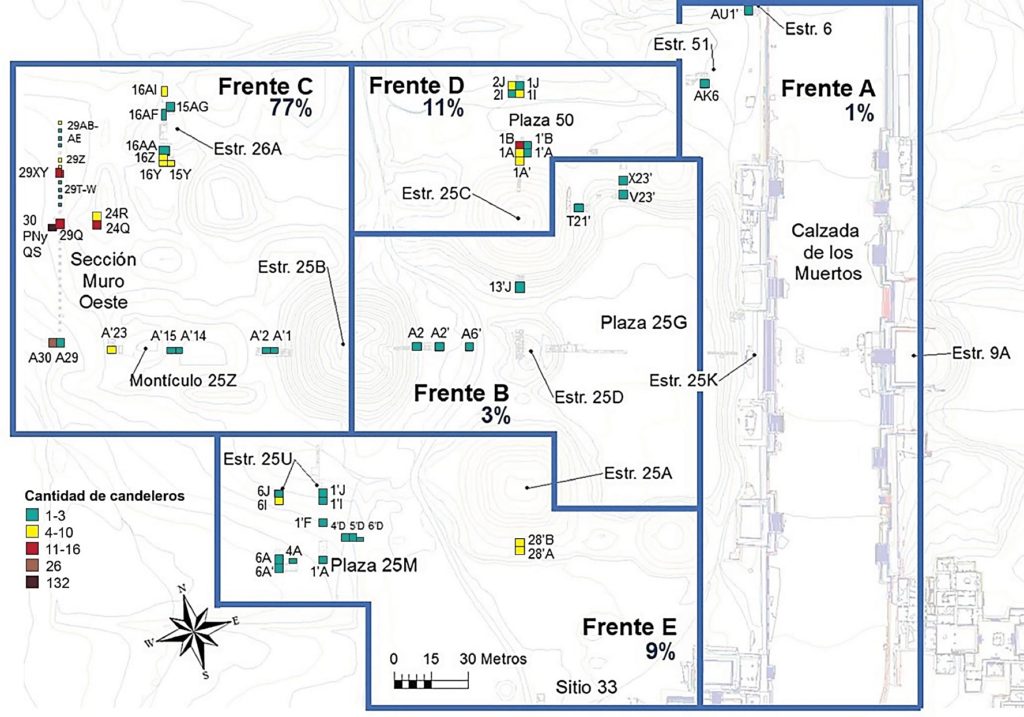

At first glance, isotope analysis is intimidating to someone with little experience with heavy machinery and chemicals. However, since working at the Archaeological Sciences Lab, I have greatly enjoyed my time learning about isotopes and the many questions about ancient life that can be answered through this process. Stable isotopes open a new window into ancient life that tell archaeologists about more than just food consumption. At the PPCC, isotope analysis has helped investigators find out more about animal management and how it had affected social structure in ancient Teotihuacan. The potential use of isotope analysis is quite vast, and archaeologists still have much more to discover using this fascinating methodology.

References:

- France, Christine A.M., Douglas W. Owsley, and Lee-Ann C. Hayek. “Stable Isotope Indicators of Provenance and Demographics in 18th and 19th Century North Americans.” Journal of Archaeological Science 42 (2014).

- Schwarcz, H.P, M.J. Schoeninger. “Stable Isotopes of Carbon and Nitrogen as Tracers for Paleo-diet Reconstruction.” In Handbook of Environmental Isotope Geochemistry, by M. Bakaran, 725-742.

- Sugiyama, Nawa, A.D. Somerville, M.J. Schoeninger. “Stable Isotopes and Zooarchaeology at Teotihuacan, Mexico Reveal Earliest Evidence of Wild Carnivore Management in Mesoamerica.” Plos One 10, no. 9 (2015).

- Sugiyama, Nawa, William L. Fash, and Christine A.M. France. “Jaguar and Puma Captivity and Trade among the Maya: Stable Isotope Data from Copan, Honduras.” Plos One 13, no. 9 (2018).

- White, Christine D. “Stable Isotope and the Human-Animal Interface in Maya Biosocial and Environmental Systems.” Archaeofauna 13 (2004). 183-198.